ABSTRACT

Acute cholangitis is a critical medical condition requiring prompt intervention. This case report explores the complexities and uncertainties encountered in clinical decision-making when faced with a patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute cholangitis. We emphasise the importance of considering individual circumstances and factors in the diagnostic process. A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn’s colitis presented with abdominal pain, jaundice and leukocytosis. Initial evaluation raised suspicions of acute cholangitis, but unexpected findings of blast cells in the peripheral smear led to a diagnosis of B-lymphoblastic leukaemia with BCR-ABL1 fusion. Treatment with steroids and chemotherapy resulted in the resolution of liver abnormalities. This case underscores the necessity of comprehensive assessments for obstructive jaundice and highlights the potential diagnostic challenges posed by underlying haematologic malignancies. It also raises awareness about drug-induced liver injury, and emphasises the importance of complete blood counts and differentials in the initial workup. Healthcare providers should be vigilant in considering alternative diagnoses when faced with obstructive jaundice, as misdiagnosis can lead to invasive procedures with potential adverse events.

LEARNING POINTS

- This case highlights the significance of conducting a thorough initial assessment when a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of liver involvement, such as abdominal pain, jaundice and leukocytosis. In this case, the patient’s initial symptoms were initially attributed to potential cholangitis due to her clinical presentation, but a peripheral smear unexpectedly revealed blast cells, leading to a diagnosis of B-lymphoblastic leukaemia.

- The case demonstrates that haematologic malignancies can manifest with various patterns of hepatic involvement, and their presentation can be diverse. In this instance, obstructive jaundice was caused by leukaemic infiltration of the liver, which is a rare initial presentation of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL).

- This demonstrates the diagnostic challenges in identifying rare conditions such as leukaemic infiltration of the liver, emphasising the importance of appropriate investigations and consultation with specialists.

KEYWORDS

ERCP, B-ALL, intrahepatic cholestasis

INTRODUCTION

Acute cholangitis is a potentially life-threatening condition that requires immediate treatment to prevent fatal outcomes. It is estimated that there are fewer than 20,000 reported cases of acute cholangitis in the United States each year, with the majority of cases occurring in individuals aged 50 to 60[1]. As the Tokyo Guidelines outline, urgent biliary decompression is strongly recommended when a patient presents with Charcot’s triad and meets the criteria for moderate to severe cholangitis[2]. Following the Tokyo Guidelines helps minimise false positive results and improves diagnostic accuracy[3]. However, there are situations where clinical decision-making becomes complex and is not straightforward. Our case study explores the challenges and hesitations encountered when making treatment decisions due to various confounding factors. This case underscores the importance of considering individual circumstances and factors in decision-making.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn’s colitis and on adalimumab presented with progressively worsening upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, a change in urine colour and chills. The patient had recently completed a course of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for an upper respiratory tract infection, and was recovering from an alcohol use disorder. On presentation, she was afebrile and haemodynamically stable. On examination, she had bilateral scleral icterus and was not in acute distress. The abdomen was distended, soft, and tender to palpation. Splenomegaly and hepatomegaly were also detected, with the liver measuring 5 cm below the costal margin.

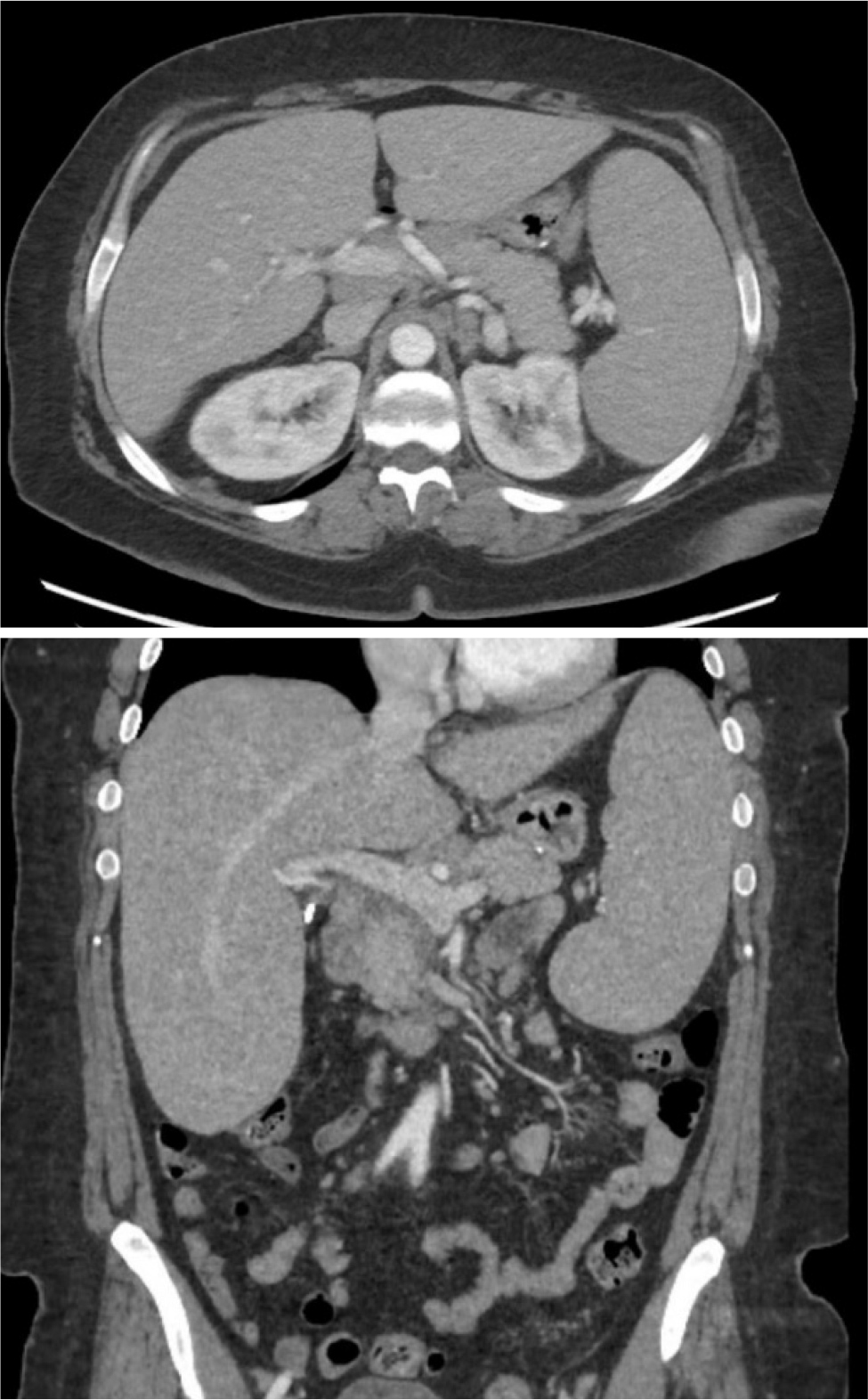

Laboratory results revealed lymphocytic leukocytosis (16 K/ul), thrombocytopenia (59 K/ul), and elevated liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase 316 U/l, total and direct bilirubin 7/6.3 mg/dl, AST/ALT 72/131 U/l) (Fig. 1). Despite the history of alcohol consumption, elevation in transaminases did not fit the clinical picture of acute alcoholic hepatitis. To further evaluate her condition, a computed tomography (CT) abdomen pelvis scan and ultrasound of the liver with doppler were performed, which showed normal common bile ducts, intra- and extrahepatic biliary ducts, and moderate hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 2).

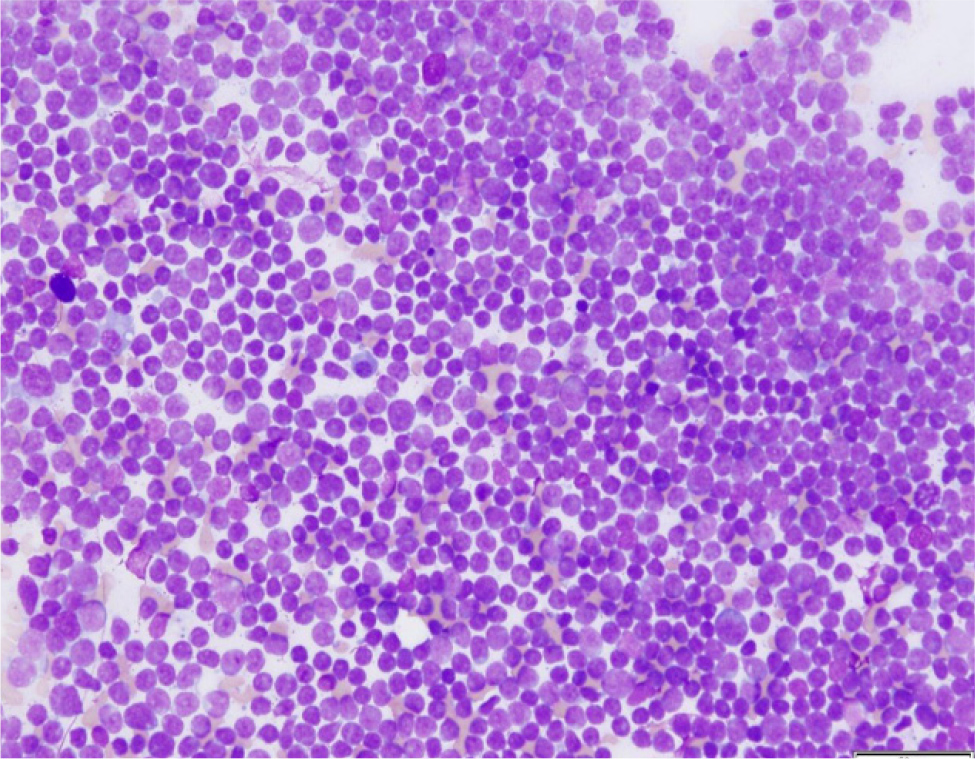

Due to the patient presenting with symptoms of abdominal pain, jaundice and leukocytosis, the gastroenterology team was consulted to assess the potential presence of cholangitis and to decide on the necessity of endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP). However, the initial evaluation took an unforeseen turn when a peripheral smear was ordered to investigate acute thrombocytopenia and unexpectedly revealed blast cells, drastically altering the clinical outlook. Subsequent investigations, including flow cytometry and bone marrow biopsy, confirmed a diagnosis of B-lymphoblastic leukaemia with BCR-ABL1 fusion, accounting for 97% of cellularity on the differential count.

Due to the initial high liver function test results, the patient required the initiation of steroids, followed by treatment with rituximab and Hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone) with the dose adjusted based on liver function/T bilirubin levels. Additionally, the patient commenced dasatinib due to a positive Philadelphia chromosome, while rituximab was administered for the CD20+ status. Following this treatment, the patient’s liver enzymes returned to normal levels.

DISCUSSION

B-cell lymphocytic leukaemia is a haematologic cancer that arises in the bone marrow and has the potential to spread to other organs through metastasis. Our case underscores the significance of carefully determining the underlying cause of obstructive jaundice in individuals with acute leukaemia, while maintaining a comprehensive approach during the initial assessment. We also considered the potential of drug-induced liver injury from amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, as the patient had recently used this medication for a respiratory tract infection and there were concerns about mixed cholestatic-hepatocellular injury, as previously reported[16]. The case also strongly emphasises the critical role of conducting a complete blood count and differential as part of the initial workup for any patient displaying symptoms suggestive of liver involvement.

Importantly, it should be noted that the patient was also receiving adalimumab, a medication that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has associated with a potential risk of inducing lymphoma and malignancies, especially in children and adolescents. Intrahepatic cholestasis in haematologic malignancies is not infrequent, though it is rarely the initial presentation. B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-cell ALL)[6,9] and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-cell ALL)[10] rarely exhibit symptoms of jaundice, making the initial presentation with obstructive jaundice a rarity. While a few cases have been observed in the paediatric population, even fewer have been reported in adults[11]. Very few cases of cholestatic hepatitis due to diffuse sinusoidal infiltration of the liver have also been reported in acute myeloid leukaemia, which also happened in our case[17].

Based on an analysis of liver specimens from an autopsy series published in 1995, it was discovered that in untreated patients with leukaemia and lymphomas, neoplastic involvement was observed in 44% of cases. Additionally, among patients who underwent chemotherapy, either as a standalone treatment or in conjunction with radiotherapy, 26% exhibited comparable indications of neoplastic presence in the liver[5]. Malignant biliary obstruction predominantly stems from cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma[15]. Other contributing factors include hepatocellular carcinoma, gallbladder carcinoma and lymphoma as in our patient.

Haematologic malignancies can manifest with varying patterns of hepatic involvement. Some patients may remain asymptomatic, with hepatic lesions being incidentally discovered. However, certain individuals may present alarming signs and symptoms of acute hepatic failure[4,7,13,]. The pathophysiology of obstructive jaundice in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) can vary. It can encompass a spectrum of mechanisms, ranging from the obstruction of the biliary duct, as observed in a case of acute myeloid leukaemia[8], formation of a bile duct stricture in a case of B-ALL[18], to the infiltration of hepatic sinusoids by tumour cells, as seen in the present case. According to certain authors[8], prednisone can be considered before initiating chemotherapy as a treatment approach. Once bilirubin levels have started to decrease, chemotherapy can be administered[12]; our patient followed a similar treatment course in this regard. Haematologic malignancies should always be considered as a possible cause in patients presenting with constitutional symptoms and hepatosplenomegaly. While a liver biopsy and immunohistochemical stains can confirm the diagnosis by revealing immature B-cell lineage, it is not always necessary, as demonstrated in the aforementioned case. Systemic chemotherapy is the primary treatment modality for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoblastic lymphoma (B-ALL/LBL).

CONCLUSION

Leukaemic infiltration of liver causing intrahepatic cholestasis as in our patient can be a diagnostic dilemma. Establishing the correct diagnosis has important implications since the treatment of choice for the alternate diagnosis – ERCP – is not only invasive but also has high risk of adverse events[14]. By carefully discerning the cause of obstructive jaundice, healthcare providers can make informed decisions regarding treatment options and optimise patient care.