ABSTRACT

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (Anti-NMDAR) encephalitis is a rare autoimmune disease, characterized by the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms. It is sometimes mistaken for a psychiatric disorder and other times not considered in the differential diagnosis of an encephalitic process. Correct identification of this disease and prompt treatment are key for optimal recovery, which might take weeks to months. Many patients manifest severe symptoms, with depressed level of consciousness, breathing dysfunction and dysautonomia requiring admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). We report the case a young male patient with anti-NMDA encephalitis who presented typical neuropsychiatric symptoms. Despite being diagnosed and treated in a timely manner, he did not respond well to first-line immunotherapy and was admitted to the ICU with neurological, respiratory, and cardiovascular dysfunction. This resulted in prolonged hospital admission and many infectious complications. Despite the severity of the disease, the patient managed to recover in the months following discharge from hospital.

LEARNING POINTS

- Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is a clinical entity described relatively recently, typically manifesting as a neuropsychiatric disorder and which should be in the differential diagnosis of any case of encephalitis, especially in young patients.

- Important prognostic factors for anti-NMDA encephalitis are lack of clinical improvement within the first four weeks of treatment and need for admission to the ICU.

- Anti-NMDAR encephalitis is a severe disease with good response to immunotherapy, hence the importance of a correct diagnosis. Nonetheless, recovery from severe disease may take months to years.

KEYWORDS

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis, neuropsychiatric symptoms, immunotherapy

BACKGROUND

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (Anti-NMDAR) encephalitis manifests as a neuropsychiatric syndrome, characterized by the presence of cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) IgG antibodies that target the GluN1 subunit of the NMDAR[1]. It is a rare disease, mainly affecting children and young adults, with a median age at onset of 21 years and a female to male ratio of 4:1[1,2,3]. Men and children tend to have non-paraneoplastic disease while ovarian teratomas are found in up to half the female patients[2,3].

In adult-onset anti-NMDAR encephalitis, psychiatric manifestations, such as aggression, irritability, emotional lability, hallucinations, catatonia or marked changes in the sleep/wake cycle, are the most common presenting symptoms. After a few days, neurological abnormalities ensue, including language impairment, memory deficits, orofacial and limb dyskinesia, delirium, amnesia and seizures[2,3,4]. Autonomic instability is also a key feature of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, characterized by sialorrhea, hyperthermia, fluctuations in blood pressure, tachycardia, bradycardia and prolonged cardiac pauses[1,2,3,5]. Up to 70% of patients are admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)[1].

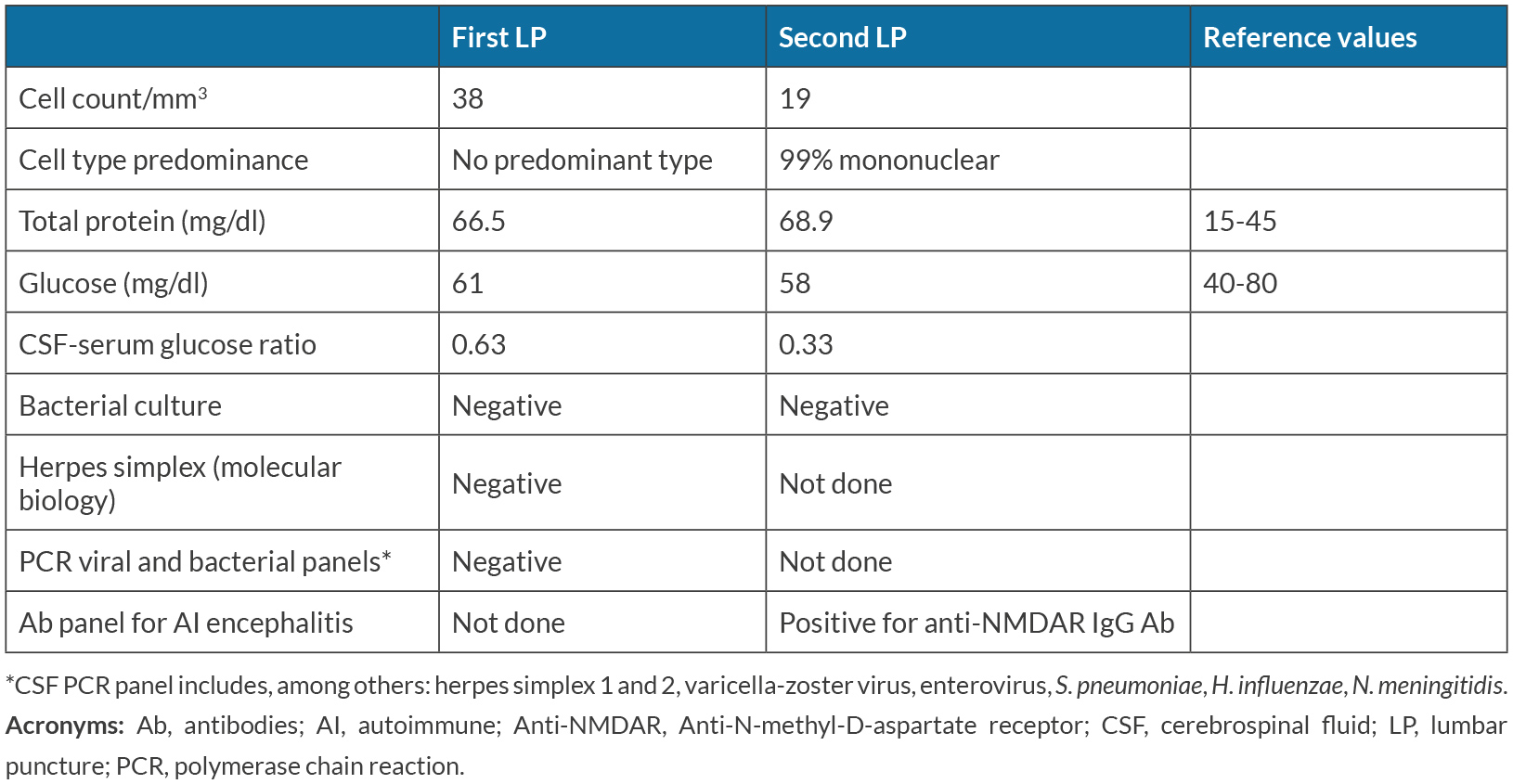

CSF analysis usually shows mild to moderate lymphocytic pleocytosis and increased protein levels[2,3,5].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) findings may be normal or show non-specific features[2,3].

Definitive diagnosis is made when the patient presents typical neuropsychiatric symptoms and has positive anti-NMDAR antibodies in the CSF and serum, after exclusion of other causes of encephalitis[1].

The current treatment approach includes immunotherapy and removal of the immunological trigger (such as an ovarian teratoma or another tumor) when applicable[3]. First-line immunotherapy involves corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange while second-line therapy includes rituximab and cyclophosphamide[4].

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient was an active 25-year-old male with past medical history of congenital macrocephaly with hydrocephalus since childhood. He presented to the emergency department with behavioral changes that had been worsening in the past few hours, with insomnia and language impairment. Physical examination was remarkable for abundant stereotypies and tics predominantly of the upper limbs, but also of the face and lower limbs. He underwent a head computed tomography (CT) scan which showed no signs of acute pathology and he was discharged with a prescription of benzodiazepine and an antipsychotic drug.

He returned the same day with worsening of symptoms, decreased level of consciousness and high fever. At physical examination he was non-collaborative, with eyes closed, miotic pupils, no conjugated eye deviation, dysarthria, and low production of speech, without apparent focal signs of neurological dysfunction. At examination he had an auricular temperature of 39.9 ºC, a blood pressure of 103/54 mmHg and a HR of 127 bpm. There were no other results of the physical exam worth noting. Blood gas analysis and blood workup were largely unremarkable, showing only mild leukocytosis with neutrophilia and slight lymphopenia but normal C-reactive protein and procalcitonin. A lumbar puncture (LP) was made and he was immediately started on ceftriaxone, ampicillin and acyclovir while results were pending. The CSF showed a slight increase in total proteins of 66.5 mg/dl and 38 cells/mm3, without a predominance of mononuclear cells (Table 1). Because these results were compatible with a viral encephalitis, acyclovir was maintained pending the PCR panel results for viral pathogens.

During the first days of hospitalization, he showed presumed episodes of focal onset impaired awareness seizures and he was started on levetiracetam and later sodium valproate.

After 5 days of acyclovir treatment and a negative CSF PCR panel, autoimmune encephalitis was suspected and a LP was repeated for antibody testing (Table 1), also done on the serum. Acyclovir was stopped and the patient was started on 1g of methylprednisolone for 5 days (beginning 5 days after admission). Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed marked bi-hemispherical cerebral activity disorganization without epileptic activity and a polymorphic continuous bilateral theta-delta activity, with delta predominance. Brain contrasted MRI showed no remarkable signal changes in brain parenchyma, particularly in the temporal lobes.

Later during hospitalization, the presence of Anti-NMDAR antibodies in both CSF and serum was confirmed, thus allowing for the definitive diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

He was later admitted to the ICU after showing signs of respiratory distress coupled with decreased level of consciousness and fluctuating heart rate. During this time, he had a low arterial blood pressure profile needing vasopressors, coupled with severe bradycardia and pauses of up to 5 seconds which coincided with moments of severe dystonia, dyskinesia and sialorrhea.

Because of the severity of the symptoms, it was decided to administer further treatment with IVIg for 5 days and 2 doses of rituximab 500mg one week apart, starting 20 days after first patient contact to healthcare.

Recovery was hindered by several infectious complications and at discharge from hospital to a rehabilitation facility, after 3 months of admission to the hospital, he retained a decreased level of consciousness, with no verbal response and no collaboration on physical exam, with bilateral stereotypical movements of the upper limbs and discrete oro-mandibular dyskinesia.

Despite the severity of the disease and clinical state at hospital discharge, the patient recovered well in the next 6 months. He was capable of executing everyday activities and had only memory lapses of the time he was admitted to the hospital.

DISCUSSION

Here we report the case of a patient with a typical set of neuropsychiatric manifestations of an autoimmune encephalitis, particularly anti-NMDAR encephalitis, and severe dysautonomia, requiring ICU admission. The usual first thought of clinicians is of an encephalitis of viral etiology, such as herpes simplex or varicella-zoster infection, and to immediately start patients on antiviral therapy. In patients less than 30 years-old, anti-NMDAR encephalitis may however be more common than other viral causes of encephalitis[5].

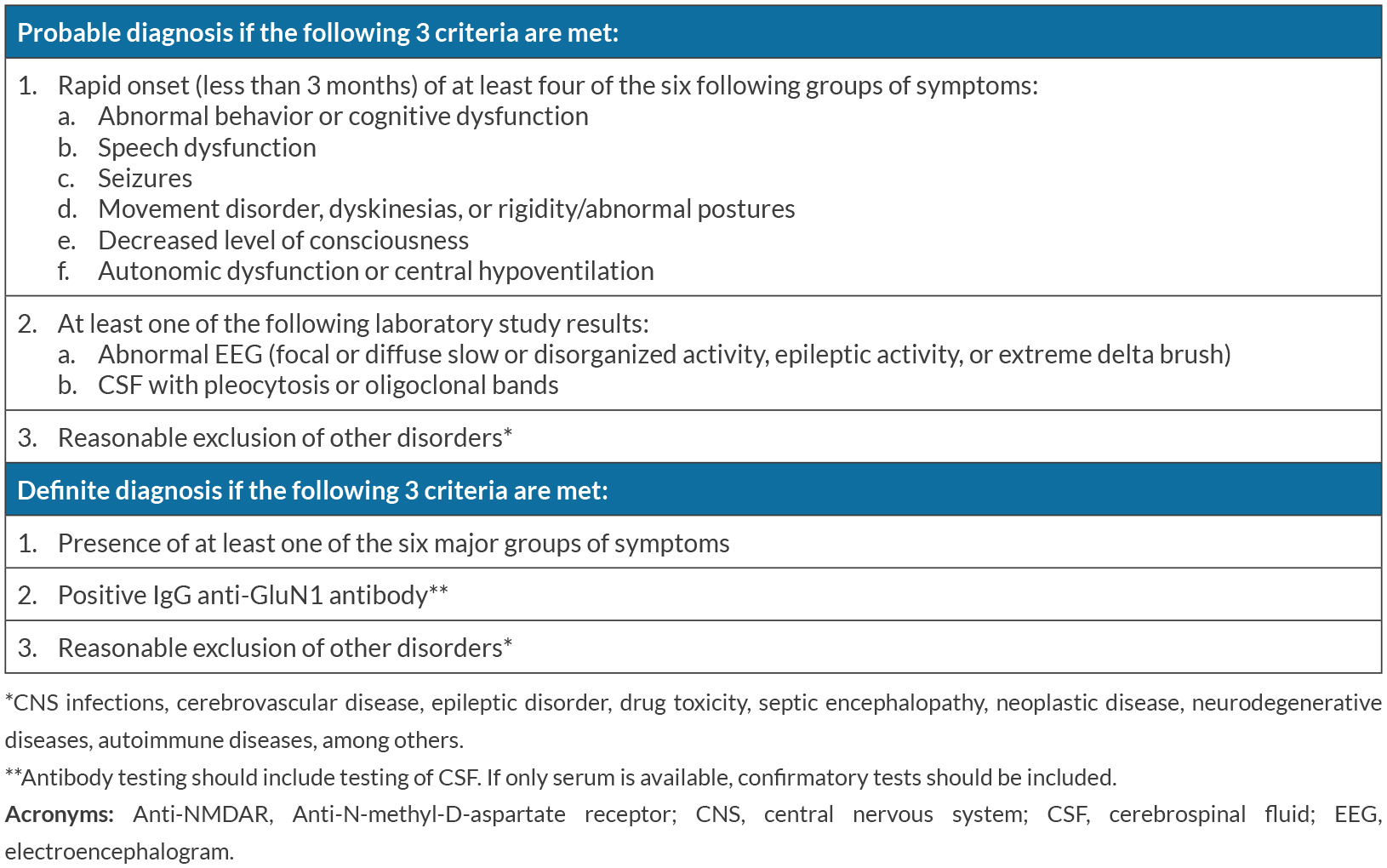

In this particular case, we are certain of a correct diagnosis as it fulfills all diagnostic criteria proposed by Graus et al. (Table 2)[6]: abnormal behavior, speech dysfunction, seizures, dyskinesias, decreased level of consciousness and severe autonomic dysfunction with subacute onset, an EEG showing cerebral activity disorganization, and mild pleocytosis and positive anti-NMDAR IgG antibody in serum and CSF (2 samples of CSF and 2 of serum, each CSF-serum pair sent to a different laboratory in different times). We excluded other possible disorders as there was no evidence of central nervous system infection, no systemic infection at time of first suspicion and initiation of treatment, no use of drugs (licit or illicit) prior to disease manifestation, no neoplastic disease (the patient was submitted to a CT scan of chest, thorax and abdomen and a scrotal echography), no epileptic disorder, negative 4th generation HIV test, no rheumatologic/autoimmune disease, no signs or symptoms of systemic immune disease and negative antinuclear antibody titer. Another factor to account for is the gradual but excellent response to treatment.

Table 2. Probable and definitive diagnostic criteria for anti-NMDAR encephalitis (adapted from Graus et al., 2016[6])

Flanagan et al. explore[7] the dangers of misdiagnosing a disease as being an autoimmune encephalitis. The dangers include failure to treat the true disease afflicting the patient and thus increasing morbidity and mortality, adverse reactions from immunosuppressant treatment the patient doesn’t need, and increase in medical expenses from ordering expensive antibody panels as well as cancer screening[7]. Most patients with a misdiagnosis do not fulfill the criteria defined by Graus et al.[6] for possible autoimmune encephalitis (72% of patients misdiagnosed)[7], which are less strict than the criteria used for defining anti-NMDAR encephalitis, fulfilled by our patient. Also, the median age of symptom onset in patients misdiagnosed with autoimmune encephalitis is 48 (IQR 35.5-60-5)[7]. Our patient was 25 years-old. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis affects children and young adults more often than older people[1,4]. In Flanagan et al.’s case series, of a total of 107 patients only 10 (9%) had a misdiagnosis of anti-MMDAR encephalitis and of these 10 patients only 4 had positive CSF antibody (3% of total misdiagnosis)[7].

Early recognition and diagnosis of an autoimmune encephalitis is of extreme importance, contributing towards the final goal of optimal immunotherapy and better outcomes. In young patients, the association of psychiatric and neurological symptoms, with non-specific EEG and MRI findings and mild to moderate CSF pleocytosis and protein levels should always raise the hypothesis of an autoimmune encephalitis and should motivate physicians to order a CSF and serum antibody panel.

Factors associated with good outcome are no need for intensive care unit admission, early treatment and low severity of disease on the first 4 weeks[4]. Despite symptom severity, rapid diagnosis and treatment result in improvement or full recovery in a majority of cases[3].

In this case, although the diagnosis was not delayed and immunotherapy was initiated in the first 4 weeks of disease onset, clinical manifestations were severe and the patient required admission to the ICU with life-threating dysautonomia, conveying a poor prognosis, which was confirmed later by a very prolonged stay at the hospital and slow recovery of neurological deficits. In this case it was decided to administer first and second-line immunotherapy in the first 4 weeks of admission, which may be the best treatment strategy in the most severe cases.

We believe this to be an important case report as it promotes awareness to this rare clinical entity, as well as to other autoimmune encephalitides, that are sometimes mistaken for psychiatric symptoms in young patients. This disease should always be part of the differential diagnosis of a case of encephalitis, as prompt initiation of treatment allows for a better prognosis and a faster recovery.