ABSTRACT

An 82-year-old man was examined using chest computed tomography after treatment for pneumonia. Imaging showed a nodular shadow in the left lower lobe with associated enlarged lymph nodes. A polypoid tumour was observed on bronchoscopic examination, and the histological findings showed pulmonary small cell carcinoma with infiltration of CD3-positive and CD8-positive lymphocytes. The patient declined any antitumoural therapy and experienced an exacerbation of heart failure treated with atrial natriuretic peptide. Eighteen months after the diagnosis, the polypoid tumour had disappeared. T lymphocyte-mediated immunity and the antitumoural effects of atrial natriuretic peptide may have influenced the observed spontaneous regression.

LEARNING POINTS

- Spontaneous regression of pulmonary small cell carcinoma is an exceptional phenomenon.

- T lymphocyte-mediated immunity and the administration of atrial natriuretic peptide may have affected the observed spontaneous regression of pulmonary small cell carcinoma.

KEYWORDS

Spontaneous regression, pulmonary small cell carcinoma, T lymphocyte-mediated immunity, atrial natriuretic peptide

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous regression of malignant disease is an unusual phenomenon and extremely rare in primary pulmonary carcinoma. The mechanism of this phenomenon has not been elucidated. We present a case of spontaneous regression of pulmonary small cell carcinoma 18 months after the diagnosis and discuss possible mechanisms that may explain this extraordinary phenomenon.

CASE DESCRIPTION

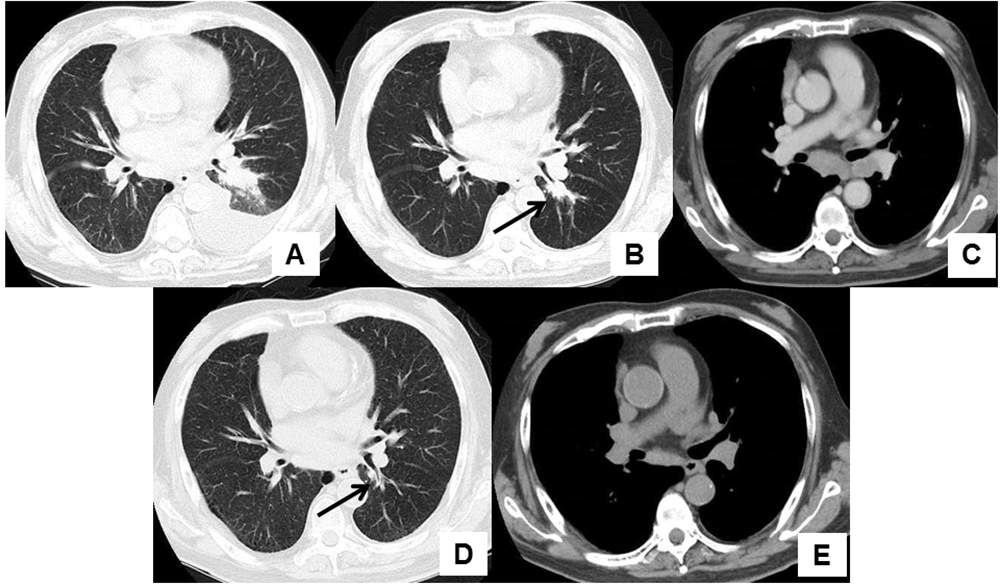

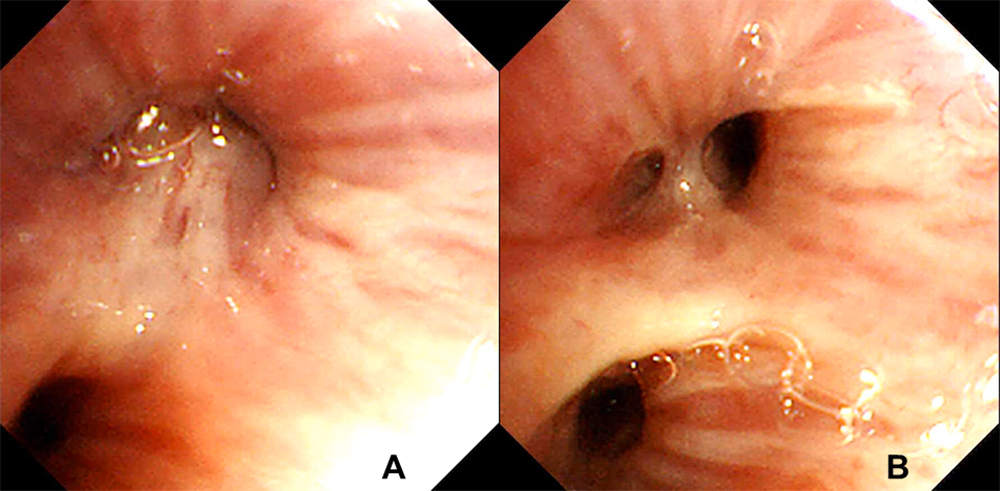

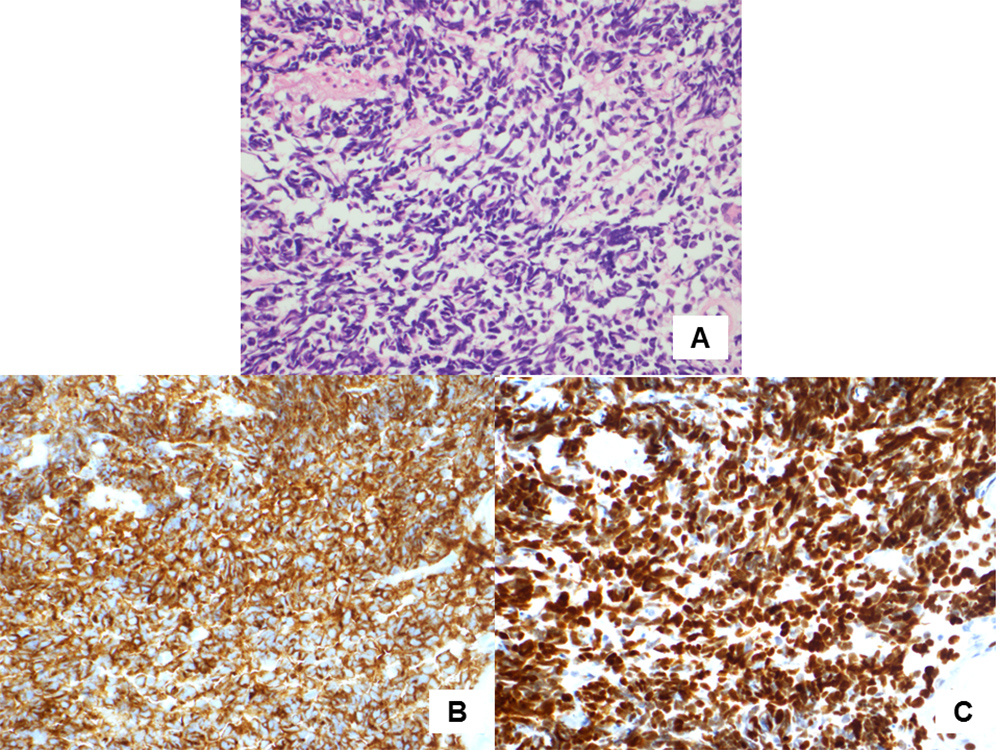

An 82-year-old man presented to our hospital complaining of cough and dyspnoea. He routinely took vildagliptin for diabetes mellitus, aspirin and carvedilol for ischaemic heart disease which had required percutaneous coronary intervention 8 years previously, and received a leuprorelin injection every 3 months for prostate adenocarcinoma diagnosed 3 years previously. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest revealed a left-sided pleural effusion and infiltration in the left lower lobe (Fig. 1A). The patient was diagnosed with pneumonia accompanying congestive heart failure and his symptoms disappeared after administration of antibacterial agents and diuretics. A chest CT scan 3 months after initial presentation showed a nodular shadow in the left lower lobe with enlarged mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes (Fig. 1B,C). The patient’s plasma pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (Pro-GRP) level was elevated at 387.2 pg/ml (normal range <81.0 pg/ml). Bronchoscopic examination revealed a polypoid tumour which occluded the left lower B6 b+c bronchus (Fig. 2A). Transbronchial biopsy of the tumour was performed and pathological examination showed small cell carcinoma (Fig. 3A–C). After whole-body examination, the small cell carcinoma was staged as cT1bN3M0. Chemotherapy was recommended, but the patient and his wife declined because of his decreased physical strength and cognitive function.

Figure 1. (A) Left-sided pleural effusion and infiltration in the left lower lobe were observed on the first visit. (B) A nodular shadow (arrow) was observed in the left lower lobe 3 months after initial presentation. (C) Enlarged subcarinal and left hilar lymph nodes were observed 3 months after initial presentation. (D) A nodular shadow in the left lower lobe had disappeared (arrow) 18 months after the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma. (E) A decrease in the size of the previously enlarged subcarinal and left hilar lymph nodes was observed 18 months after the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma

Figure 2. (A) A polypoid tumour occluded the lumen of the left lower B6 b+c bronchus. (B) The polypoid tumour disappeared and the lumen of the left lower B6 b+c bronchus could be visualized

Figure 3. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining showed proliferation of atypical cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (400× magnification). (B) Synaptophysin immunostaining was positive (400× magnification). (C) Thyroid transcription factor 1 immunostaining was positive (400× magnification)

After the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma, routine follow-up was performed every month. During follow-up, the patient was hospitalized twice. The first admission was due to exacerbation of chronic heart failure, which occurred 7 months after the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma. Diuretics including carperitide, a recombinant form of α-human atrial natriuretic peptide, were administered and he was discharged 19 days after admission. The second admission was due to hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state and occurred 9 months after the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma. The patient’s blood glucose level was 818 mg/dl on admission; insulin therapy was administered, and he was discharged after 13 days of hospitalization.

Eighteen months after the diagnosis of pulmonary small cell carcinoma, the patient’s chest CT showed disappearance of the nodular shadow in the left lower lobe and a marked decrease in the size of the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes (Fig. 1D,E). Bronchoscopic examination showed disappearance of the polypoid tumour which had previously occluded the left lower B6 b+c bronchus (Fig. 2B). His plasma Pro-GRP level also decreased to 91.7 pg/ml.

DISCUSSION

In the present case, pulmonary small cell carcinoma spontaneously regressed 18 months after its diagnosis. Spontaneous regression of malignant disease is recognized as either a partial or complete disappearance of the disease without appropriate treatment[1]. Occurrence of this phenomenon has been reported to range from 1 in 60,000 to 1 in 100,000 cases[2]. In particular, spontaneous regression of primary pulmonary neoplasms is extremely rare. Kumar et al. reviewed case reports concerning spontaneous regression of thoracic malignant disease from 1951 to 2008; only five cases were primary thoracic neoplasms including mesothelioma, while 71 cases were metastatic thoracic neoplasms[3].

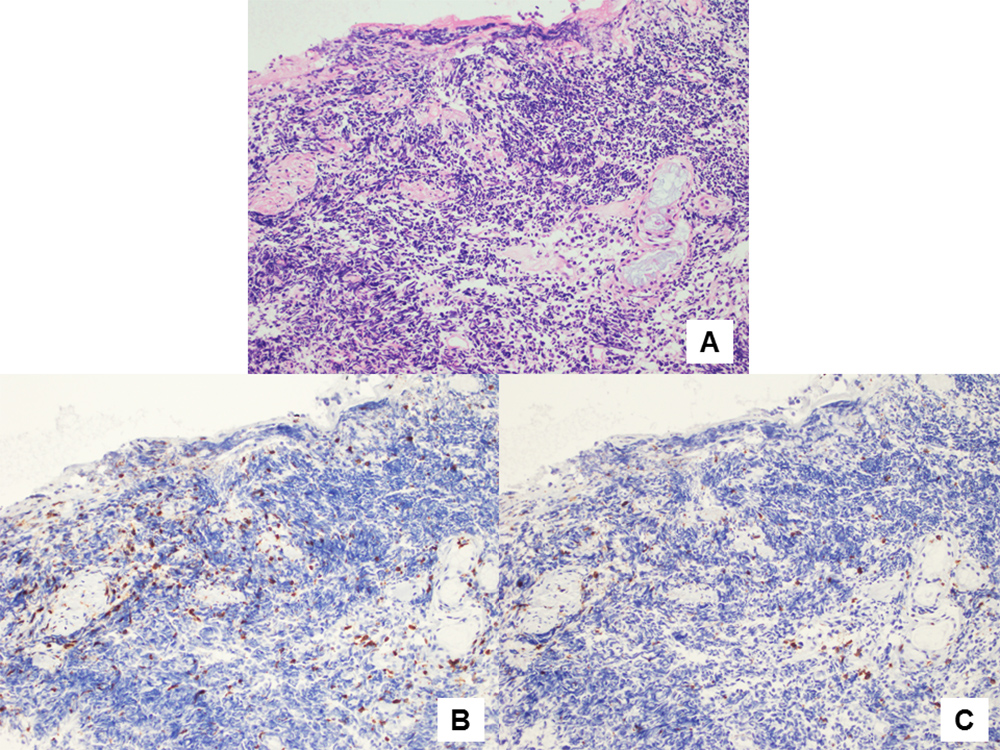

The exact mechanism of spontaneous regression of malignant diseases is unclear. However, it is considered to be related to apoptosis and activity of the immune system[4]. Recent reports have shown that high-density infiltration of T lymphocytes on pathological examination of cancer specimens was associated with a favourable clinical course in patients with lung cancer[5]. Cluster of differentiation (CD) 3, a cell surface co-receptor protein related to the T lymphocyte receptor, is regarded as a marker of all T lymphocyte types, while CD8 is known as a specific marker of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Tokunaga et al. reported a case of spontaneous regression of breast cancer with axillary lymph node metastasis which had strong infiltration of CD3-positive lymphocytes in the tumour nodule[6]. We examined infiltration of T lymphocytes in the present case using immunostaining of rabbit anti-human CD3 antibody and mouse anti-human CD8 antibody (Dako, an Agilent Technologies company, Denmark). Examination of the specimen obtained through transbronchial biopsy revealed strong infiltration of CD3-positive lymphocytes and moderate infiltration of CD8-positive lymphocytes around the tumour tissue (Fig. 4A–C). Thus, T lymphocyte-mediated immunity may play a significant role in spontaneous regression of malignant diseases.

Figure 4. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin staining showed proliferation of small cell carcinoma cells (200× magnification). (B) Immunostaining using rabbit anti-human CD3 antibodies showed strong infiltration of CD3-positive lymphocytes (brown) around the carcinoma cells (200× magnification). (C) Immunostaining using mouse anti-human CD8 antibodies showed moderate infiltration of CD8-positive lymphocytes (brown) around the carcinoma cells (200× magnification)

Our patient experienced two hospitalizations in the follow-up period. The first admission was due to exacerbation of chronic heart failure requiring intravenous administration of carperitide, a recombinant α-human atrial natriuretic peptide. This peptide has previously been reported to possess antitumoural effects. An in vitro study performed by Skelton et al. showed that atrial natriuretic peptide induced death in human prostate and pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells without damaging healthy prostate, kidney and lung cells[7]. In mouse models, atrial natriuretic peptide inhibited the adhesion of cancer cells to pulmonary micro-vascular endothelial cells[8]. These antitumoural effects of atrial natriuretic peptide may be involved in the spontaneous regression in the present case.

The second admission during the follow-up period was due to hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state requiring insulin therapy. A hyperglycaemic state can provide abundant energy through amplified glycolysis and result in proliferation of cancer cells[9]. Moreover, insulin therapy has been reported to be a potential risk factor for the development of colorectal cancer because of its stimulation of cellular proliferation [10]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports in the literature of a positive relationship between spontaneous regression of malignant disease and hyperglycaemic state requiring insulin therapy.

In conclusion, we presented a case of spontaneous regression of pulmonary small cell carcinoma. Although the exact mechanism has not been elucidated, T lymphocyte-mediated immunity and the antitumoural effect of atrial natriuretic peptide may have induced the observed spontaneous regression.