ABSTRACT

Cancer is associated with a higher risk of stroke, and in rare cases stroke can be the first manifestation of occult neoplasia. We present the case of a 74-year-old woman hospitalized for ischaemic stroke with multiple cerebral infarctions in several vascular territories. The exclusion of other aetiologies and the simultaneous presence of thromboembolic events in other organs raised the suspicion of a hypercoagulable state, which upon investigation revealed occult neoplasia of the lung. There was rapid deterioration, with recurrent thrombotic events despite anticoagulation, which eventually led to the patient’s death.

LEARNING POINTS

- Stroke can be the first manifestation of occult neoplasia.

- In the presence of cryptogenic stroke, high D-dimers, multiple brain infarctions in different vascular territories and thromboembolic events in other organs, the possibility of hidden neoplasia should be considered.

- Anticoagulation in disseminated intravascular coagulation is insufficient if the primary disease is not treated.

KEYWORDS

Stroke, lung cancer, disseminated intravascular coagulation

CASE PRESENTATION

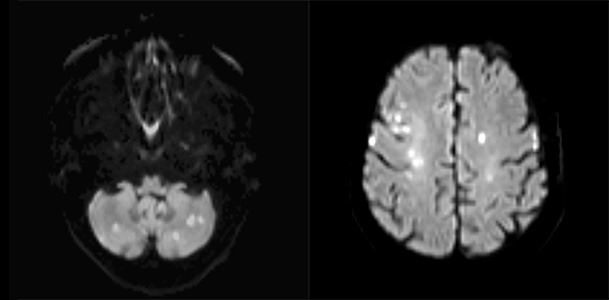

A 74-year-old woman, with controlled hypertension and dyslipidaemia, presented to the emergency department due to altered speech, left-sided facial droop and decreased muscle strength on the right side of her body with 12 hours of evolution. Physical examination showed aphasia, central facial nerve palsy on the left side, slight right-sided hemiparesis, Babinski’s sign on the left and fever. Computed tomography of the head (head-CT) showed bilateral nucleocapsular and subcortical fronto-parietal ischaemic infarctions of unknown date. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm and the thorax x-ray a small left pleural effusion. Blood analysis showed 14,400 leucocytes/µl, increased C-reactive protein (217.8 mg/l), LDH 459 U/l and INR 1.57. The patient was medicated with aspirin and hospitalized with ischaemic stroke. Blood cultures were collected. Doppler ultrasonography of the neck vessels and a trans-thoracic echocardiogram showed no alterations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple acute ischaemic infarctions scattered over both cerebellar and cerebral hemispheres, reflecting strokes in the posterior and anterior circulations (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance of the brain showing multiple acute ischaemic lesions in the anterior and posterior circulations

Given the possibility of cardioembolic aetiology, enoxaparin was initiated (on the 7th day of hospitalization), however transoesophageal echocardiography showed no alterations. Neurological deficits deteriorated on the day anticoagulation was started, leading to prostration. Head-CT was repeated, revealing a massive parenchymal haematoma in the left frontal region which led to suspension of the enoxaparin.

After the most common stroke aetiologies were excluded, the following examinations were performed, but showed no alterations: lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibodies, antithrombin III, proteins S and C, antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies, mutation of the prothrombin gene and factor V Leiden, and HIV, HBV, HCV and VDRL serologies. Antinuclear antibodies were positive (1:160) and D-dimers were high at 1,644 µg/l (normal <230 µg/l), while fibrinogen was low at 1.4 g/l (normal 2–4 g/l).

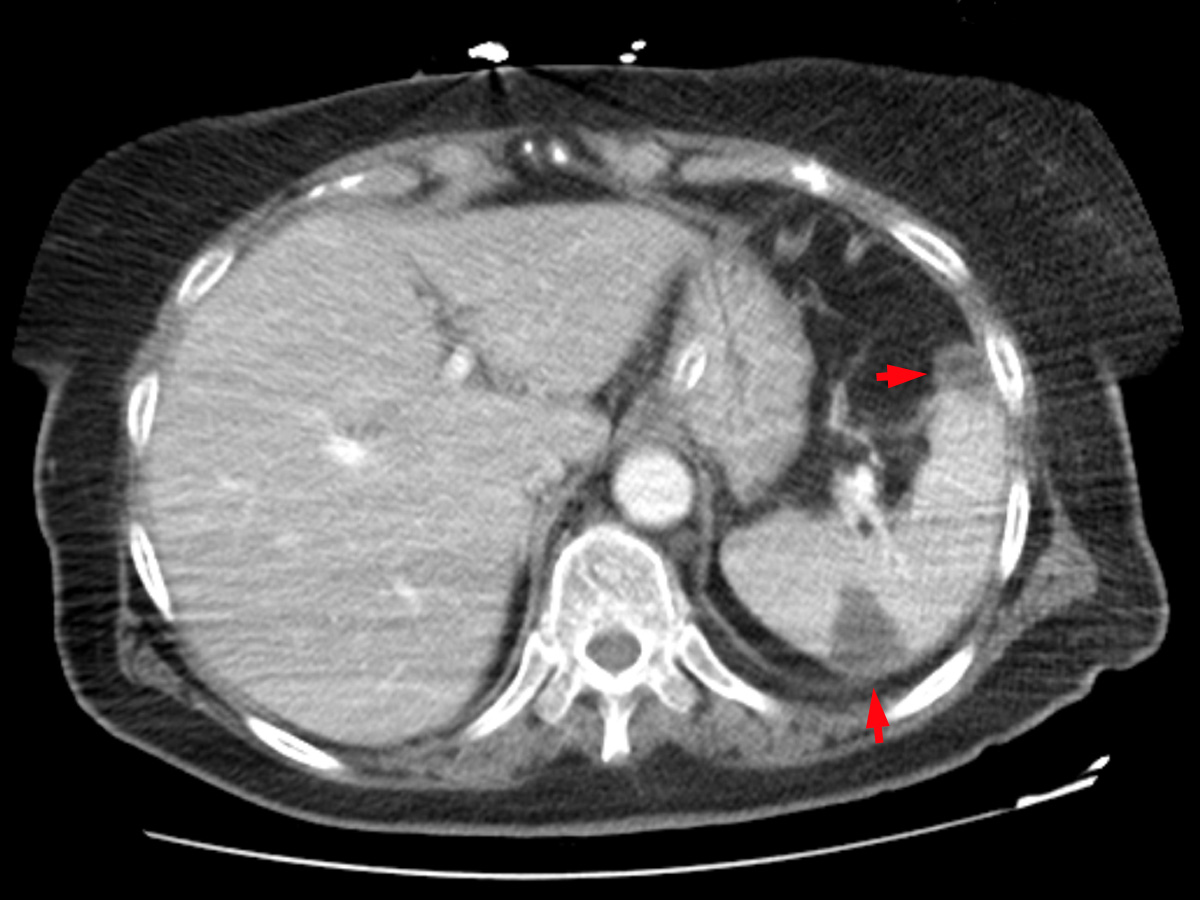

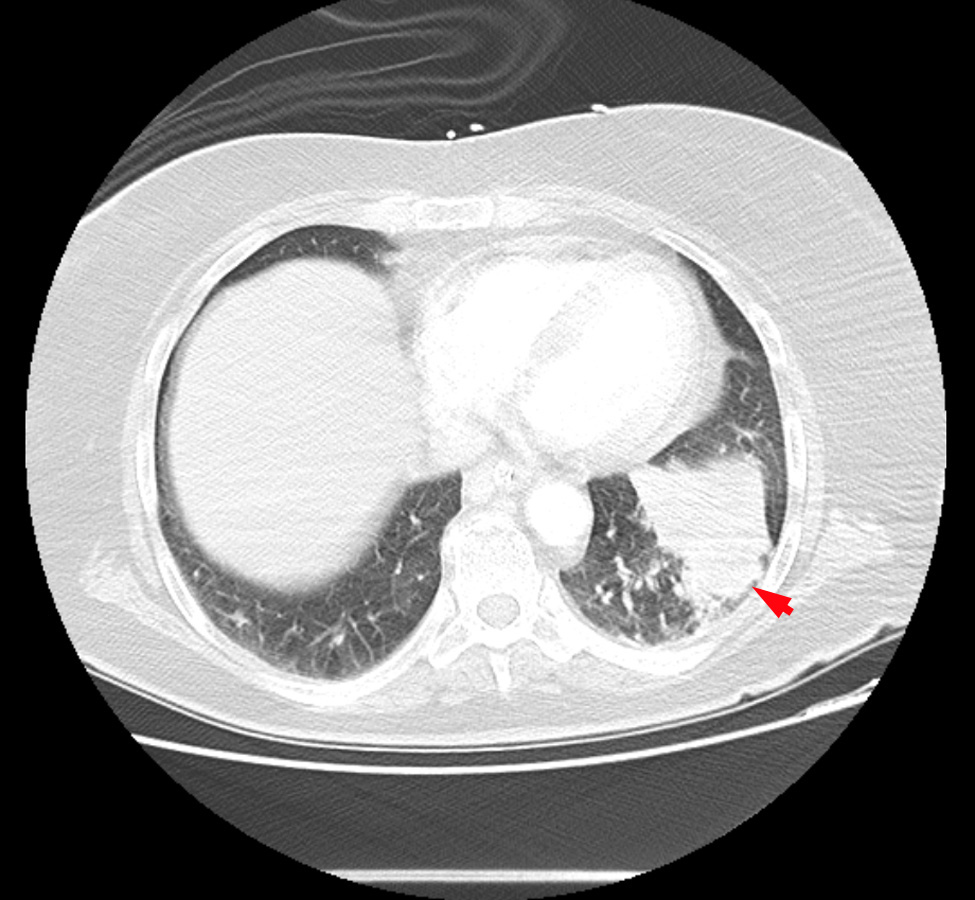

A whole-body CT scan revealed a solid lesion in the left lower lobe of the left lung, multiple mediastinal pathological lymph nodes, peripheral lung thromboembolism with greater expression on the right, right femoropopliteal venous thrombosis and splenic and renal infarctions (Figs. 2–4).

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showing splenic infarcts (red arrows)

Figure 3. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showing kidney infarcts (red arrows)

Figure 4. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the thorax showing lung cancer in the left lower lobe (red arrow)

Faced with the impossibility of resuming anticoagulation immediately, a filter was placed on the inferior vena cava. Cerebral angiography showed occlusion of the right internal carotid artery (recall previous normal Doppler ultrasonography of the neck vessels) and excluded vasculitis.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transoesophageal biopsy of a mediastinal lymph node revealed non-small cell lung cancer. Immunohistochemistry testing for the lung cancer subtype proved inconclusive.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with multiple brain and systemic thrombotic events was diagnosed as a manifestation of a paraneoplastic syndrome of the hidden lung neoplasia. With favourable evolution of the brain haemorrhage, enoxaparin was resumed 2 weeks after the event. However, as there were new thromboembolic events despite the reintroduction of anticoagulation, it was definitively suspended due to progressively worsening thrombocytopenia.

During hospitalization, the patient remained feverish, with high inflammatory parameters, but no infectious source was identified and microbiological cultures were negative. Such alterations were considered to be correlated with systemic thromboses.

At this stage, the patient was mute and tetraparetic, with a level 4 performance status (ECOG). It was decided in a multidisciplinary meeting not to start cytostatics as no benefit was anticipated in view of the advanced neoplasia (stage IIIB/IV) and a high degree of dependence. The patient was referred to palliative care and died a few days later.

DISCUSSION

Stroke, just as venous thromboembolism (VTE), can be the first manifestation of hidden neoplasia and precede its diagnosis by several months[1,2].

Although the most frequent aetiology of stroke in cancer patients is related to traditional cerebrovascular risk factors, cryptogenic stroke is more frequent in this population[3]. In some cancer patients, stroke has certain particular characteristics suggesting underlying pathophysiological mechanisms other than the traditional ones, pointing towards a more direct role of cancer in the genesis of the stroke[2,3]. This patient had several cancer-associated ischaemic-stroke (CAIS) characteristics: cryptogenic stroke with fewer traditional cardiovascular risk factors, multiple acute ischaemic lesions in different cerebral vascular territories, high D-dimers and the simultaneous presence of other thromboembolic events[2,3]. The presence of high inflammatory parameters also appears to be a characteristic of patients with CAIS[4]. A stroke patient with these characteristics should therefore raise the hypothesis of hidden neoplasia.

The hypercoagulability associated with cancer seems to be the most important mechanism in the genesis of CAIS and may manifest in its most severe form with DIC, a poor prognostic factor in lung cancer[1,3,5]. In this patient, paraneoplastic DIC was responsible for VTE and for multiple arterial thromboses in the brain, kidney and spleen. Even though enoxaparin may have contributed to brain haemorrhage, DIC certainly played a key role, leading not only to thrombosis but also to haemorrhage through the consumption of platelets and coagulation factors[1].

Anticoagulation is likely to be beneficial; however, the safety and efficiency of this strategy in cancer patients and DIC has yet to be evaluated in major clinical trials, and cases like that here portrayed illustrate how this therapy can be hard to manage[1,3], The treatment of neoplasia is crucial for the resolution of DIC[1,5].

Even though cancer patients are especially vulnerable, there is still a need for guidelines regarding both the prevention and treatment of stroke in this population[2].