ABSTRACT

A 23-year-old woman, a smoker and oral oestrogen user, presented with nasal necrosis. No other symptoms or local trauma were described. Relevant laboratory findings included complement consumption, positive lupus-anticoagulant assay, increased rheumatoid factor and positive cryoglobulins. Screening for autoimmune conditions, haematological malignancies and infectious diseases was negative. Histological examination of the nasal skin showed small vessel occlusion without vasculitis. Later, a second positive lupus-anticoagulant assay supported the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome. The patient improved with glucocorticoids and anticoagulation. This case report describes an unusual manifestation of antiphospholipid syndrome in a patient with cryoglobulinaemia contributing to the thrombotic event and highlights the importance of recognizing these overlapping disorders.

LEARNING POINTS

- Nasal skin necrosis is an uncommon event with a wide spectrum of aetiologies.

- The rare association of antiphospholipid syndrome with cryoglobulinaemia may act synergically in small- medium vessel occlusion, with skin involvement being the most common manifestation.

- Anticoagulation and immunosuppression of antiphospholipid syndrome with cryoglobulinaemia is mandatory.

KEYWORDS

Cutaneous necrosis; antiphospholipid syndrome; cryoglobulinaemia

CASE PRESENTATION

The authors present the case of a 23-year-old Caucasian nulliparous woman taking a combined oral contraceptive. There was no relevant past medical or family history apart from active smoking.

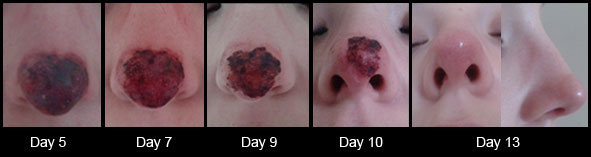

Two days before hospital admission, the patient noticed a small purplish spot on the tip of her nose that progressively increased to a necrotic cutaneous lesion associated with local paraesthesia, without areas of ulceration (Fig. 1). She had previously been exposed to cold temperatures during a winter night out. She denied fever or other systemic symptoms, previous local trauma or inhaled cocaine abuse.

A local biopsy was performed. Laboratory investigations revealed a slight normocytic normochromic anaemia (haemoglobin 11.5 g/dl), an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (83 mm/1st-h), complement consumption and a positive lupus-anticoagulant assay, so the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) was considered. The patient also had increased rheumatoid factor (140 IU/mL) and positive cryoglobulins, making the diagnosis even more challenging. Antinuclear antibodies, anti-double stranded, extractable nuclear antigen and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. Screening for haematological malignancies, other thrombophilias, hepatitis C and B viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis and other infectious diseases was also negative.

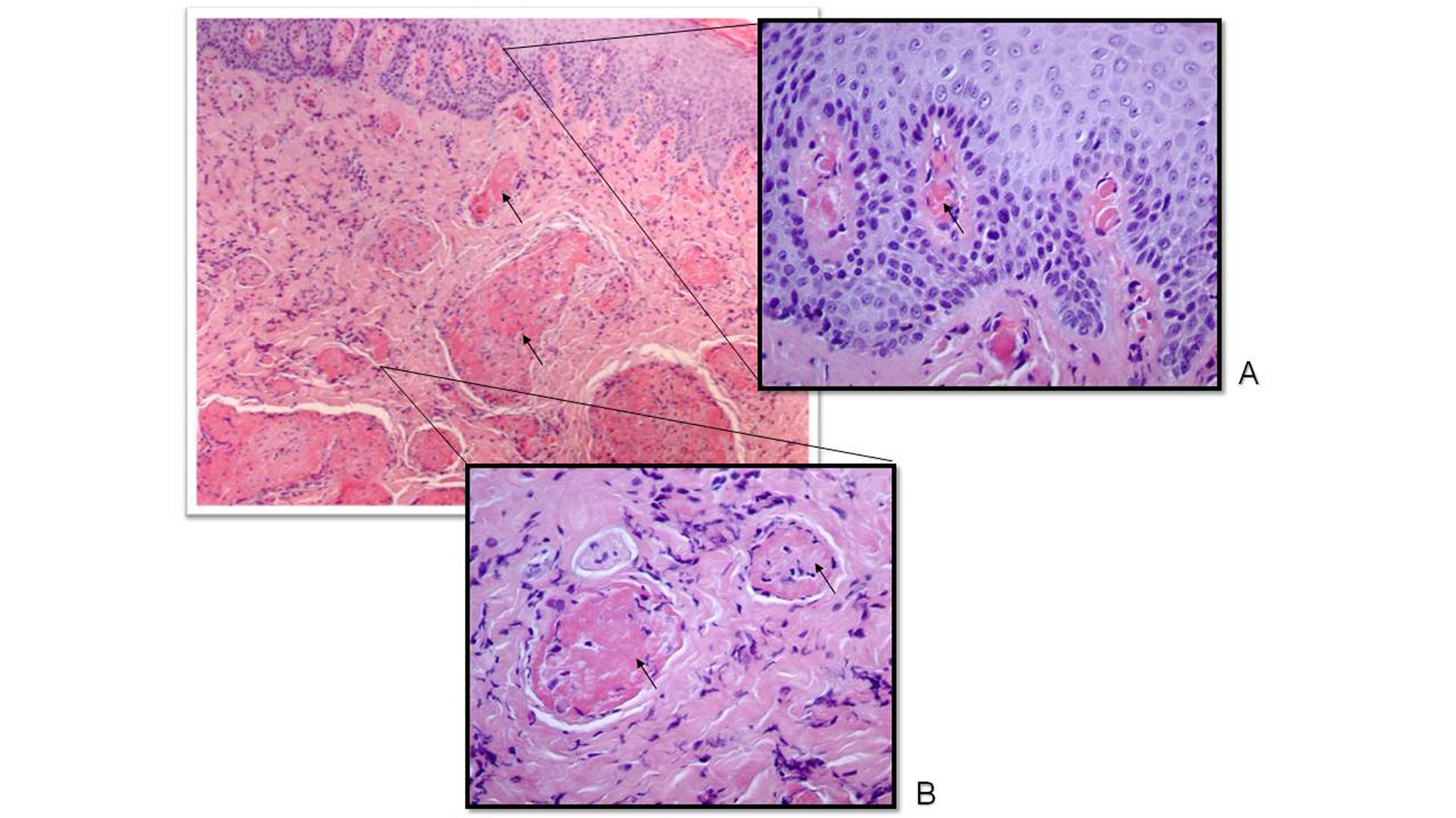

Histological examination revealed small vessels of the dermis filled with homogeneous eosinophilic material (fibrin), with no evidence of vessel vasculitis (Fig. 2 A, B).

Thirteen days after hospital admission, the patient had recovered with total re-epithelialization of the necrotic area, after treatment with methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 3 days), followed by slow tapering of prednisolone, and anticoagulation Figs. 3 and 4). She received counselling for contraceptive method choice and was advised to stop smoking. On discharge, she was referred to Internal Medicine for consultation.

After 8 months, another positive lupus-anticoagulant assay and persistent negative results for cryoglobulins were obtained, so anticoagulation and a low dose of prednisolone were continued. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient is asymptomatic.

Figure 1. Patient with nasal skin necrosis on day of admission to the Internal Medicine department

Figure 2. Skin biopsy (haematoxylin and eosin stain). Small-sized vessels of the papillary dermis (A) and reticular dermis (B) occluded with homogeneous eosinophilic material corresponding to fibrin (arrows). There is no evidence of vasculitis on vessel walls

Figure 3. Nasal skin necrosis after 3 days of methylprednisolone (1 g/day). The peripheral areas of the lesion have improved

Figure 4. Evolution of skin necrosis over 13 days under hypocoagulation and immunosuppression

DISCUSSION

This case report describes an unusual location of a thrombotic event in a patient with APS and a rare association with positive serum cryoglobulins. This complex case also highlights the importance of performing a thorough clinical investigation without compromising prompt treatment.

Nasal skin necrosis has an extensive differential diagnosis. At first approach, attention should be given to excluding trauma, local or systemic infection, autoimmune disease and malignancy. Since infectious and autoimmune aetiologies have different treatments which can have harmful side-effects, it is crucial to rule out other diagnoses before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, as performed in this case.

APS is an autoimmune disorder characterized by all size venous or arterial vessel thrombosis in the presence of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (one test around the time of the event and a later confirmation after at least 12 weeks). APS is either a primary disorder or secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It can involve most systems and cutaneous necrosis has been described[1].

The authors had a strong clinical suspicion of a thrombotic aetiology, in this necrotic event in a young woman with a positive lupus-anticoagulant assay and other established risk factors (smoking and oestrogens)[2] The diagnosis of primary APS was corroborated by histopathological confirmation of thrombosis, with no evidence of inflammation in vessel walls and with the second positive lupus-anticoagulant assay some months later.

Cryoglobulinaemia should be considered in a patient with positive cryoglobulins (precipitable serum immunoglobulins at temperatures below 37ºC) causing a systemic inflammatory syndrome. It results in small or medium-sized vessel damage due to hyperviscosity (often secondary to lymphoproliferative diseases) or mediated by immune-complex vasculitis (mainly associated with infections or systemic autoimmune diseases)[3].

In this patient, cold exposure before development of the skin lesion, positive cryoglobulins and increased rheumatoid factor were regarded as relevant factors, so all possible cryoglobulinaemia- associated diseases were excluded. However, previous studies have recognized a rare association between cryoglobulinaemia and APS with cutaneous involvement as the most common manifestation, suggesting a synergic effect of serum cryoglobulins in small- medium vessel occlusion[4]. In those studies, cryoglobulinaemia was detected in patients with APS or APS secondary to SLE.

This case illustrates the complexity of the diagnostic approach to a vascular event and the need for a stepwise investigation to identify the underlying cause.

While waiting for laboratory results and histopathology, clinicians must decide on initial treatment according to clinical presentation. Once APS is considered to be the cause of a thrombosis event (except in obstetric APS), anticoagulation should be started with heparin and bridged to warfarin for an international normalized ratio target of 2-3. In the presence of cryoglobulinaemia, immunosuppression and/or plasmapheresis should be provided according to clinical severity and evolution.

Treatment of APS can decrease thrombotic predisposition, but patients remain at risk for recurrent events[5]. The course and prognosis of cryoglobulinaemia varies, depending on vital organ involvement[3]. Little is known about the clinical course of these combined disorders.

Based on elevated rheumatoid factor and positive cryoglobulins (suggesting mixed cryoglobulinaemia associated with autoimmune diseases), the presence of complement consumption and the known overlap of cryoglobulinaemia, SLE and APS, we expect that this patient might develop other autoimmune manifestations in the future[6].